Storytime Lets Fathers Form Bonds From Behind Bars

Across the country, inmates are distance-reading bedtime stories to their kids and finding their own paths to redemption.

By Ludwig Hurtado

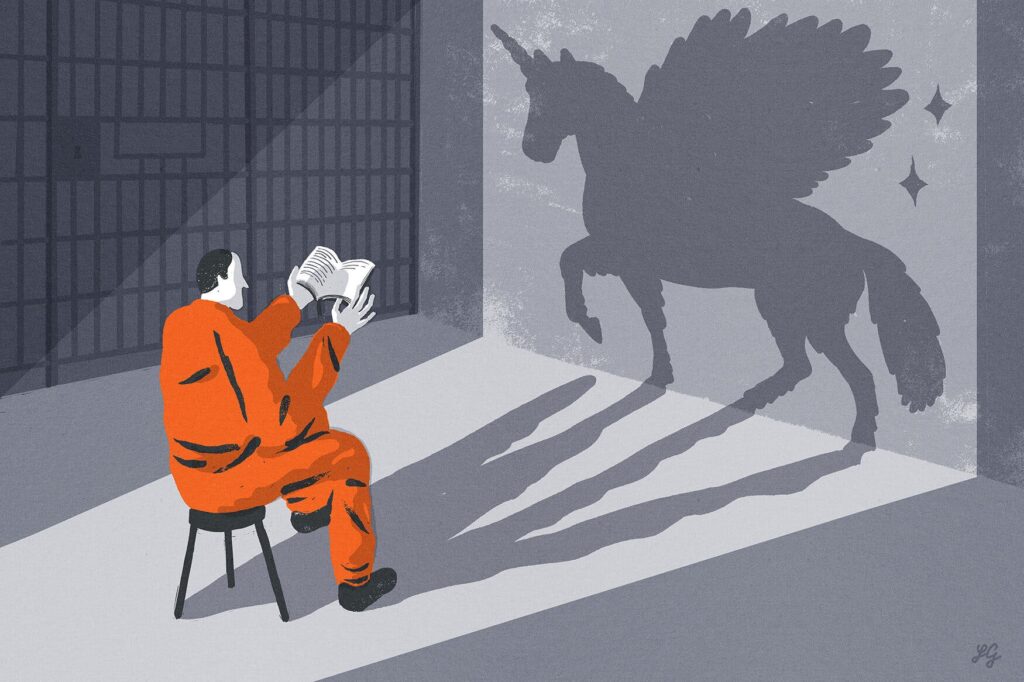

Art by Lorenzo Gritti

Greg Williams, 45, doesn’t remember the first book he read to his daughters in 2006, but he remembers picking the shortest book in a stack, hoping he could get to the end without crying on camera. He imagined his girls in their pajamas, tucked into bed, listening. As he turned each page, he imagined that he was there, too.

At the Descanso Detention Facility in Southern California, a dozen men waited with tough-guy facades and children’s books in hand. They were participants in a program that allowed incarcerated parents to read to their children, albeit far removed from their bed sides. An unassuming beige room at the jail became a makeshift production studio, with men taking turns in front of a tripod-mounted camera.

One by one, dads shape-shifted from guys in prison garb to dragons, wizards and even princesses. They contorted their voices, becoming heroes from faraway lands, where fairies were real and fathers weren’t locked away in dungeons.

For those who are incarcerated, parenthood can feel nearly impossible. They miss out not only on the big soccer matches, music recitals and school dances that shape childhood, but also the peanut butter and jelly sandwiches, board games and nightly bedtime stories.

While they may never be able to see that game-winning soccer goal in person, inmates across the country are at least trying to bridge the storybook gap for their families, aiding not just their kids’ development but also their own.

A New Chapter for Incarcerated Parents

While it sounds simple, reading to your child can have profound impacts. In 1985, a report by the National Academy of Education concluded that, for children, reading aloud was the most consequential factor in their educational success down the road. Since then, countless studies have touted the cognitive and behavioral benefits of reading aloud to children.

But the benefits of reading programs for incarcerated parents go beyond cognitive benefits. For many, it’s less about literacy, and more about mending and maintaining their bonds that are strained by their being behind bars. Building this bond is more crucial now, because the pandemic has limited access to family members over the past year, though restrictions are easing in some places.

At the Carol S. Vance Unit prison near Richmond, Texas, Caleb Ester chose to read “The Jungle Book” for his daughter’s 11th birthday in 2018, because she told him that she loved animals. Squeezed into an audio recording booth, Mr. Ester, 38, was participating in the inmate-run Storybook Dad program, which was started by a former inmate in the Prison Fellowship Academy.

After recording, program volunteers added sound effects and then sent the C.D., along with a copy of the book, for his kids to read along.

Because he was incarcerated before her birth, Mr. Ester said his relationship with his daughter was always different from that of other inmates. His daughter has dyslexia, which he said makes it all the more important that he encourage reading. Until he could be by her side, he said the recordings and books were “like a piece of me laying with her.”

Eventually they developed a routine during visitation. Every time she’d go to see him, she’d bring a book for them to read together.

Mr. Ester was released in November 2019 and is now living with his mother and daughter in Houston. While they are still adjusting to life under one roof, Mr. Ester said that he still reads to his daughter almost every night.

Transforming On and Off the Page

For Mr. Williams, that day he first read to his daughters was the beginning of a greater transformation. From 1993 to 2005 he’d been using methamphetamines and cycling in and out of jail.

As much as he tried to be a good father, Mr. Williams said he couldn’t escape the streets, violating his probation or committing a new felony. Then he’d find himself in a living room, explaining to his girls that Dad had to go on “time out” again.

“I had to sit them both down and tell them I was going away to where dads go when they’ve been bad,” Mr. Williams recounted. When it was too hard to say goodbye, he’d say he was going to return a movie or buy cigarettes, and disappear for months. Then, during a parenting and anger management class in jail, a classmate suggested Reading Legacies.

The San Diego-based organization was founded by a retired teacher and was originally aimed at recording deployed military parents reading to their kids. But the organization eventually saw a greater need among incarcerated parents.

There are an estimated 2.7 million children in the United States with incarcerated parents. According to a 2015 study by the nonprofit research firm Child Trends, Black children were nearly twice as likely to have a parent incarcerated than white children. Other research indicates children with incarcerated parents have an increased risk of depression, addiction and poverty, and they are six times more likely to end up incarcerated themselves.

Sociologists have found that parenting education programs in general improve inmate recidivism in parents and self-image in children. Other research suggests reading programs in particular are effective.

“We tend to define people by the worst thing they’ve ever done,” said Heath Hoffmann, a sociologist at the College of Charleston who studies the effectiveness of prison programs. “But programs like these help incarcerated people occupy a role other than ‘criminal.’”

In a survey of 387 state-run correctional facilities across the country in 2010, Dr. Hoffmann found that 75 percent of women’s facilities and 23 percent of men’s offered programs where incarcerated parents could send their children recordings of themselves reading a book. Most wardens reported in the survey that they felt the programs improved family relationships during incarceration, reduced recidivism and made re-entry into society easier for parents, though more research is needed.

Dr. Hoffmann said the bedtime story programs allow inmates to reconcile a shameful past with a positive future. “People are able to rewrite the story of their life,” he said.

Kory Russell, a utilities foreman who said he once made “an artwork of going in and out of prison,” said that the distance reading program helped him rewrite his life. When he was sentenced to 15 months in prison in 2018, he felt that his daughters “had no choice but to be a part of my incarceration, too.”

When Mr. Russell, now 40, heard about a distance reading program it soon became both a refuge and a chance to be someone new.

“It’s like putting on your absolute best performance for the ones you love most,” he said. “Every time you read a character’s line, you do your best to turn into that character, whether it’s a little girl or a big beast.”

Kory Russell, 40, participated in the Reading Legacies program in 2017 while incarcerated at the East Mesa Correctional Facility in San Diego.

Looking for Happily Ever After

The distress of family separation has been exacerbated by the coronavirus pandemic. In order to reduce the risk of potential exposure in the facilities — which have been occasional hotbeds for viral outbreaks — most prisons and local jails have reduced or eliminated family visitation. In an effort to mitigate isolation, the Federal Bureau of Prisons made phone calls and video visitations free. In October, the bureau decided to reopen visitation, citing the importance for inmates to “maintain relationships with friends and family,” though most jails and state prisons continued to disallow visits.

According to a New York Times coronavirus database, there have been more than 612,000 infections and at least 2,700 deaths among inmates and guards since the start of the pandemic. Researchers at Johns Hopkins University found that infections in U.S. prisons were 5.5 times higher than in the general population. They also found that the coronavirus death rate was three times higher for prisoners.

Because of the pandemic, the Reading Legacies program now operates virtually, with inmates reading aloud to their kids over the phone and on video chats.

The silly faces and noises of reading a children’s story offered an escape from jailhouse culture, which Mr. Russell likened to that of a 12-step meeting or church service.

As for Mr. Williams, the bond he began fostering with his children through the pages of a book has only gotten stronger. His daughter, Melissa White, now 25, said that receiving those recordings from her father more than a decade ago opened her heart to the possibility of letting him back into her life.

“My dad being incarcerated was my normal,” she said.

Today, Ms. White is a teacher with a master’s degree in early childhood education and special education. When possible, she volunteered at her local library, reading books to children. And, she said, her relationship with her dad is the best it’s ever been.

“He is truly one of my idols and my best friend,” she said.

View live article here: https://www.nytimes.com/2021/03/11/parenting/bedtime-stories-prison.html